So, when it comes to the world of design, I know it probably sounds really cool to be able to say to your mates “Look at me, I’m a designer. See this thing I made in Photoshop? This is something i made.” and as you stand there in your cocked up turtleneck, and your Clubmasters that you specifically got in Gold and Black to really amp up the scandi look, your mates turn and think…

“Man what a dickbag. Bet he doesn’t even work for a firm.”

Truth be told, any person who has access to a graphic design tool will definitely know how to make something. Sure, you can cut out a background and make a hilarious meme about how X thing you like is funny, but how do you actually be a designer?

Well, there’s a few basic rules I find that are easy to follow. And like Fight Club, a lot of them are pretty recursive and esoteric, some contain a lot of in-jokes, and most of all, they definitely do not come with a serving of sarcasm. heh.

Rule 1: Functional things are always beautiful.

Why make something that just looks nice, when that nice thing can serve a purpose? When you’re a designer, you have to firstly learn to differentiate the difference between Art and Design.

First of all, throw the idea of “art with a purpose” out the window… Because the very first recursive thing I’m going to state is that considering that in the Year of Our Lord and Saviour, Xenu the space lizard, 2021, Art has no purpose other than itself, and it is up to the individual that perceives that artwork to decide what it means. Why is that? Well, Postmodernism, Baby! The conflict of postmodern artists is whether or not to toe the line between selling that Jackson Pollock to a billionaire for a tax writeoff for their “Gallery” or to keep your integrity intact. I kid, but in reality the very first rule of art, is that art cannot be functional for any purpose other than itself. This is why we see art as beautiful.

However, when people ask me “Hey how do you define what designers do”, I say, “design is art with a functional purpose.” in other words, what you are trying to do is to use creativity to solve problems, not make statements.

After all, this is how engineers can become pretty effective designers. They simply use a different creative toolbox. An artist will spend years honing and creating a particular style for themselves, building a groove and a niche for their gallery to communicate a cohesive message, and now you’re seeing the entire gallery standing up in arms when they realise “Hang on a second. This art’s all connected! This in and of itself is a piece of design, not art!”

…And this is where the huge postmodern snake eats it’s own poop.

The second distinction I draw is that function is explicit in design. In other words, just by visually consuming the piece you can get a pretty good idea as to what it’s job is. Nobody’s going to look at say, a pot with a plant inside it and not say that the plant is in a vase… Unless the pot looks like something else, then they’re going to say “Oh, that vase looks like an Elephant’s ballsack.”

…Then I would question what my hypothetical friends watch in their spare time.

This leads me to the final point. Functional things are always beautiful. When you design something, the very first thing you should do is to figure out what problem you’re trying to solve. Sometimes you’ve gotta put your engineer’s hard-hat on for a bit and figure out “Okay, how am I going to get a vacuum feed from this engine to the exhaust, and what spec do the threads need to be to be compatible with the large majority of fittings.”. Your typical postmodern artist would think “Modifying cars is a capitalist construct so why bother when you can simply set that car on fire to make a statement.”

Do you notice something with those three statements? This leads me onto my fourth.

Rule 2: Rules are there for a reason. Embrace them!

Okay, so now that we’ve thrown your artist’s mind aside a little bit, let’s crush your spirit even more and teach you how to embrace rules and be a good little citizen. There are reasons why designers insist so much on being systematic, it’s purely because there are actually rules to being a designer. Unspoken ones, sure. But rules nonetheless.

Now, I got told a few months ago that “I had an eye for design and layout” and that designers are “talented”, I immediately turned around and proceeded to laugh at that friend of mine. Why? Because I simply work to a set of pretty well-tested and well constructed rules in my particular discipline of work.

When say, you design a product, you are dealing with plenty of rules. Design standards exist for example to make sure that you don’t accidentally come up with a brand new type of screw-thread and make it impossible for people to find a replacement screw for when the thing you make suddenly turns into a 2005-era MySpace teenager and decides it wants to kill itself.

Maybe if my parts weren’t so insistent on listening to The Black Parade they wouldn’t be so damn sad all the time.

My point? Rules exist for a reason, and they’re there to help you, not hinder you. The reason why you use a specific screw pitch on a design for a part is to make it easier for you to find parts and it takes a step out of your working process. In graphics, there are rules about colour and contrast, weighting, space, visual flow, descriptions, and copywriting, to make it easier for designers to lay out documents, websites and the like.

Generally, a good idea that I use is to use W3C guidelines for designing websites for people with disabilities when it comes to things like designing layouts and selecting colours. Being verbose with your wording means you can get your point across (although I specifically write this way on my site because well, everyone needs a space to cut loose) , and being muted and minimalist in your design makes it easier for people to be directed to where they need to go.

I specifically chose this layout on my website (Neve) because it ticks all the boxes when it comes to rules. It’s clean, simple, and it means that with a few tweaks (I specifically prefer to use DIN style fonts as opposed to their original ones) I could make my site work for me. In my first article I wrote about making things easy, and one of the best ways to make things easier for you as a designer is to constrain yourself within a set of rules, and bloody stick to those rules.

One of the biggest gripes of interior designers and decorators is predominantly to do with people thinking they can break the rules of design. There’s reasons why the Scandinavian style works, it works because it looks pleasing, it’s functional, it’s airy and most of all, it’s easy to achieve if you stick to a few basic rules.

Zen is basically just dark scandinavian, fight me in the comments. Oh wait, you can’t.

But in mentioning that, it’s important that you at least test the borders, because…

Rule 3: Everybody sucks at something.

…Yes, even you.

Have you ever seen this diagram before?

It might look like a squiggly line on a white background that I totally didn’t spend five minutes in Illustrator whipping up or anything, but this is a pretty important graph. Mostly because if you’ve ever tried to learn anything or do anything new, you’ve probably gone through points of this graph.

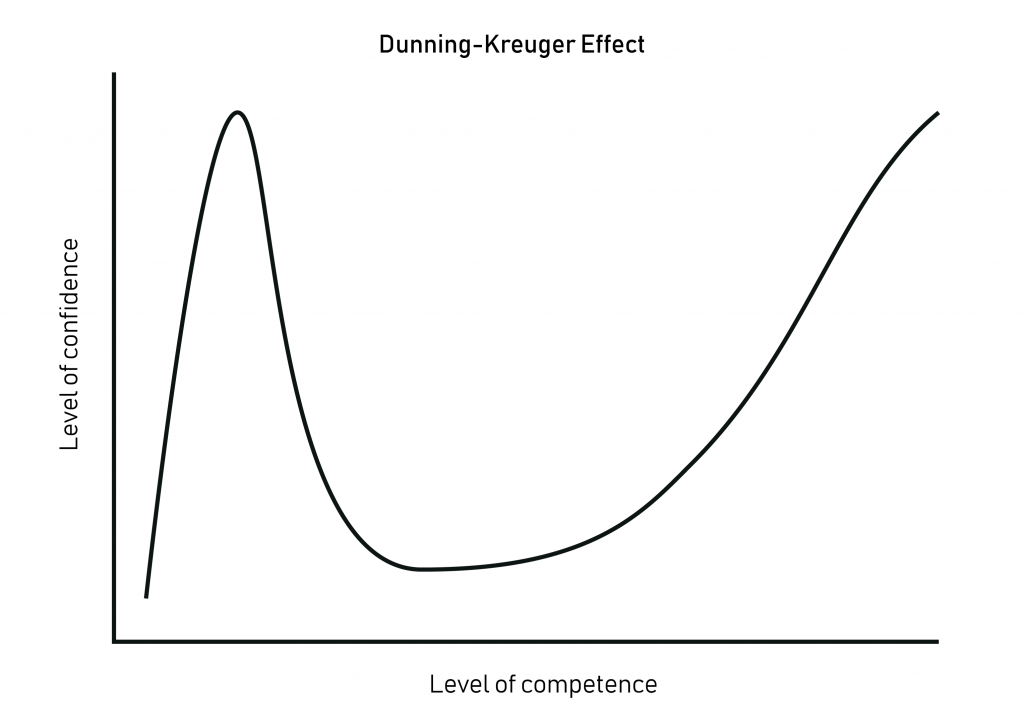

It’s called the Dunning-Kreuger effect, and it essentially plots one’s level of confidence and competence in a subject along these axes.

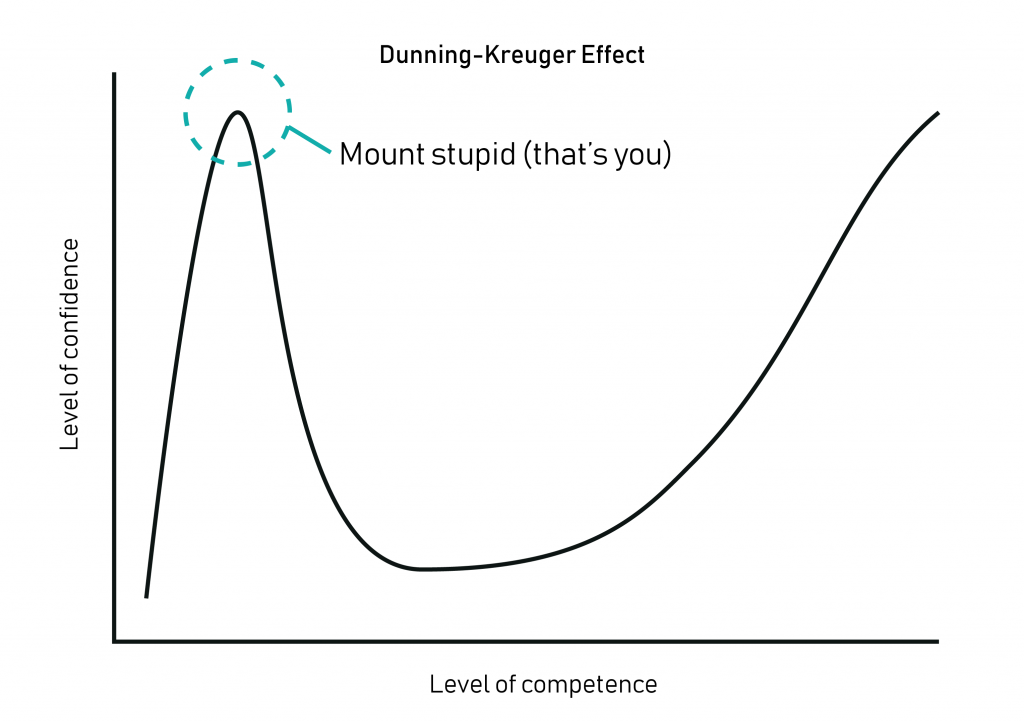

When we first begin learning something, we get this burst and surge of confidence in the topic. I remember when I first started learning to be a designer, I was sitting right up on Mount Stupid for a while. What’s Mount Stupid?

That bit, right there. The point where you think you know absolutely everything about a topic, even though you know sweet bugger-all about it. Novice designers experience this all the time, predominantly because you might’ve either scored your first paid gig, or perhaps you’ve just picked up Photoshop and you suddenly believe you can freelance and just like, make money. But there’s a very good reason as to why you’re not being paid the $75k/yr of a designer that works in a firm, or the hundreds of thousands of dollars that a design consultant gets. It’s because you suck, but you just don’t know it yet.

Now, don’t be afraid of those words. When you’re new to the game, of course you’re going to suck. You just don’t know about it until you get your first come-to-Jesus moment. That might be when a client refuses to pay for your first work, or that moment when a client is pissed that you used sub-par methodologies, or that your reskin of a poorly designed website didn’t make the customers go up 200% like you promised that small business owner. This is because competence only truly begins when you first admit that you suck… And I know it’s a cardinal sin these days to quote Self-Help Gurus, especially if Twitter has anything to do about it, but to quote Tony Robbins:

You see, in life, lots of people know what to do, but few people actually do what they know. Knowing is not enough! You must take action.

Anthony Robbins

The only way to learn how to do something and do it well, is to keep doing the damn thing, but do so knowing that you’re not the best, and never will be the best, unless you check your ego at the door and climb that damn mountain. For starters, I don’t work at Pentagram, nor do I go to SIGGRAPH every year. Will I end up climbing Mount Stupid if I ever do go to SIGGRAPH? Probably. Or maybe I might just spend half the time drooling on the Arizona printers. Who knows?

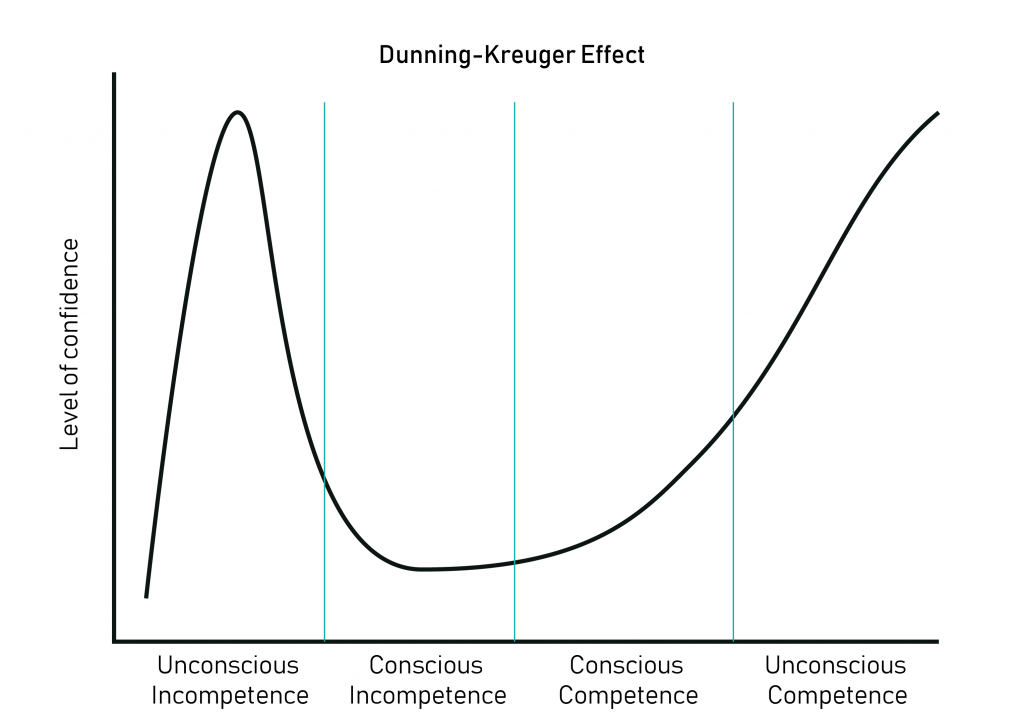

This leads me to the way to get off Mount Stupid. It’s best to break that graph into four distinct sections when it comes to learning any skill.

Mount Stupid is what I like to call “Unconscious Incompetence.” where you suck but you just don’t know it because you’re so enthralled in the new thing you think you can take on the world. Once you get vibe-checked and sent into the shadow-realm of conscious incompetence, this is where the bulk of people stop learning their skills. But those who have a passion for things, who actually want to become good at something, kill their egos and begin to take the long hike towards Unconscious competence, via a fuck-ton of conscious competence. You keep your rules in your mind, and slowly pursue that climb, knowing that this peak is never-ending. You will spend your entire career getting progressively better and better, to the point where you’re actually knowledgeable enough to become hirable by that massive design firm you’ve always wanted to work for. But before you get hired, you gotta remember one thing.

Rule 4: Stay humble, don’t let your ego kill your talent.

You’re a monk now. No, not a monkey, this isn’t memeland, this is design land. The path to unconscious competence is paved with the ability to kill that ego. Put your personal conceptions aside, and instead focus on what is needed by your client, not what you want. Your job is to help your clients visualise and put their ideas to life and to help them achieve their goals, not so you can get a little warm fuzzy for yourself. That comes at the end when you get your paycheck. As a designer, your goal is their goal. To quote Stephen Covey in his book, The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People

When one side benefits more than the other, that’s a win-lose situation. To the winner it might look like success for a while, but in the long run, it breeds resentment and distrust.

Dr. Stephen R. Covey

It’s kind of hilarious that I’m citing Habit 4 in Rule 4 of my design guide, but Doctor Steveyboy makes a good point here. If you consistently focus on what benefit you are getting from a situation, then you will constantly be at the detriment of your clientele. Clients want to hire designers because they want to focus on what makes them better.

A good example of this was when I used to work for the monument company I used to work for. I worked alongside an old bloke who was an engineer who formerly worked for a large construction company, designing material production plants. After the passing of a friend’s daughter, he used his engineering expertise to start a company that focused on producing funerary monuments using modern technology to help people preserve their memories in the way they wanted. However, this required the help of a designer who knew what they were talking about and was willing to work with an older bloke who had more pen-and-paper knowledge when it came to design.

This person had hired many designers beforehand. A freelancer whose invoice layouts made absolutely no sense when it came to flow and readability was a notable mention, and he constantly kept harping on about getting paid. Another who was completely apathetic to the work and couldn’t put his ego aside to focus on the common goal, and myself. Now granted, working with this employer was… Particularly stressful to say the least, but for the most part, it was a real vibe-check for me. It taught me the fundamental rule of working with clients. You’re both in it to win it.

This doesn’t mean that your opinions are not valid. Not at all, after all, you’re the designer, so you should at least know something about how to get something working to your client’s needs. If you don’t know, however, you’ll need to look at the way in which you work and adapt it to work.

The amount of times i’ve seen a client come in with a really low-resolution JPEG that they want engraved on a stone? I’d need as many arms as Vishnu to be able to do that. But instead of telling them to screw off, I negotiated a win-win situation out of it. I tell them “Well, despite what the TV says, Photoshop isn’t this magic program that can miraculously turn photos into ultra-sharp masterpieces. I’ll try my best to get it to work, but I can’t guarantee it’s success. I can do a test piece for you on some scrap stone to show you how it’ll look”

Nine times out of ten? My clients were perfectly fine with the image. Sure, some of those stones might not be the best designs I’ve ever done, but the clients were happy. That was a win for me (because the clients were satisfied), a win for my boss (because he got paid for the stone) and a win for them (because they got the stone they wanted). Win, win, win.

If your designs do what your customers expect, if they are to your standard of quality as far as reasonably practicable, and if they get you paid, then they’re good. Check your ego at the damn door.

Rule 5: Bob Ross is wrong, there are no happy accidents. (Design with intent)

When you design something, you need a goal, a mission and an intent and purpose. I keep repeating myself here but I’m going to keep doing so until it sticks, dammit! You know how I said that rules help? Well, the more constrained you are, the more certain of the intent of the piece you want to create. If you go on rambling tangents, you lose people and your message is made unclear, then your project will drag out on, and on, and on.

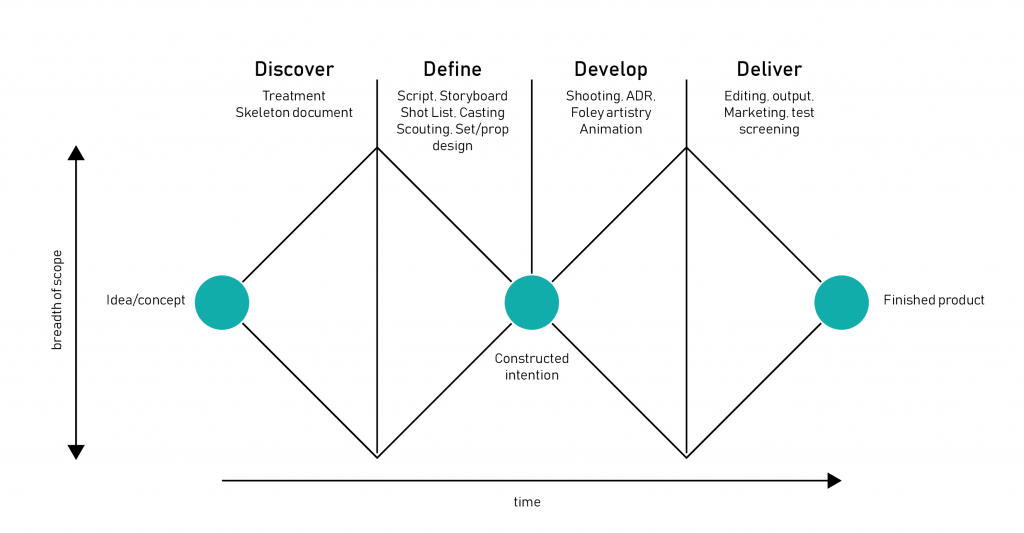

When I produce videos for example, I make sure that I intentionally stick to a process. I write a treatment document which gives me an overall scope. Then, I script, which constrains me down to dialogue and action. Then I storyboard based upon the script. That brings me down to a visual representation of what I need to capture. Then I make a shot-list. That hones me down to what shots I need. Then I go out and scout for talent to restrict me to a particular actor. I design elements of the video to hone in the visuals. Notice what I’m doing here? I’m intentionally whittling away complexity and uncertainty with every step in the process. A scope document is a wide, broad document which states the ideas for what we have in mind. The finished product is the intent of all our pre-production work.

In fact, the reason why a feature length film takes so long to produce doesn’t come from the process of production itself. That often takes the shortest amount of time in a filming process. The average feature takes between six weeks to three months of constant shooting. Why? Well, easy. Because the production company’s spent a good three years planning the principal photography of the film in order to give the cinematographer more time to make his shots look good, to give the director more ability to focus on the actors, and so on.

There’s an actual process to this, and its intent is to be expansive, and the hone things down as you go along in order to create more refined, polished projects. It’s called the 4D process.

So the idea is, we broaden the scope of a project, and as we have all our ideas together, we use processes to whittle the ideas down into a point where we intentionally restrict ourselves in order to create our end-product. Might sound like a bunch of hyper-corporate gobbledygook, but it essentially boils down to, if you intentionally craft a product you can have all the ideas in the world, but the success of your product entirely depends upon the intent of your work. The more effort you put into the honing process (to a point), the more refined and the better quality your product will be… To a point.

Obviously, if you whittle and hone your product down too much, you’ll end up completely missing the point. This intent should always be present when you are coming up with anything. To put things into perspective, If you want to make a video exposing political corruption, don’t go on huge tangents unless they are relevant. This is why FriendlyJordies, a prominent Australian YouTuber who focuses predominantly on exposing corruption in Australian Politics, is so gosh-darn effective. Everything in his videos has an intent and purpose, even the non-PC jokes he puts out. He is disregarding what the optics are and is instead focusing on grinding his axe towards the intent of the content, to take down Lib/Nat governments by any means necessary.

In fact, that brings me to comedy. The key to good comedy is to have an intent. If your intent is to be likeable, you won’t be funny. Why? Well appealing to the masses often means you have to whittle your content down to the point where you can’t intentionally say anything. Have a goddamn opinion for Pete’s sake. Your products will seem more genuine if there is a well-designed intent to them. Be it comedy, videos or car parts, so long as there is intent, there will be people who want that thing for that intent. Just remember not to let your ego kill that intent either.

Rule 6. Obsession is good, but obsess broadly.

Once again, I’ll refer back to my buddy Loomhigh like I did in the first article. I honestly think he’s a brilliant designer, not because he’s actually a designer or anything… But because he doesn’t obsess with the how, but more or less he focuses on the why. Ever wonder how he does his graphics work? If your answer was “He uses photoshop, cockbreath!” I’d firstly ask… “Hey how did Gary Orsum find my page” and secondly, I’d tell you that you’re wrong. The guy uses freaking PowerPoint to do those graphics. I know, right? Pretty innovative.

There’s a book that I reckon every aspiring filmmaker should read. It’s called Shut up and Shoot and its by Anthony Q Artis, a jack-of-all-trades who’s covered a wide gamut of video production, from producing to camera operation to direction. One of the lines from that book is pretty prominent. Now others will attribute it to Chase Jarvis, but dammit, I saw it in this book first.

The best camera, is the one you have on you right now.

Anthony Q Artis, amongst others

In other words, stop obsessing about the what, and start thinking about the how and why. I have a Sony A7s in a full cinema cage that gets only very occasional use. Why? well, I bought it to complete my university studies. I needed a camera for dramatic production, and as far as bang-for-your-buck was concerned, it fit the bill nicely. Also I find it kinda fun to collect components for it. However, both Jordan Shanks (FriendlyJordies) and Loomhigh share one thing in common, they’re resourceful and use what’s available to them. Filming on a cheap $50 camera from K-Mart? You better believe that’s more ideal than wasting your time obsessing over cameras and not actually producing any content.

What’s better is to obsess on ideas. As a graphic designer, don’t focus on the tools. There’s plenty of Photoshop alternatives. MS Paint can be a powerful tool in the hands of a competent user. As a writer? Use what you have already. Hell, George RR Martin still writes using WordStar on an old DOS PC. Why? Because he’s already familiar with it, why change for something newer when you’re already a master at your work.

If you give yourself missions, you’ll use your tools to your advantage. You should only feel the need to switch tools if your current tools do not provide you with the ability to achieve your mission goals. If CorelDRAW works for you, why switch? If it suits your design style or works for the purpose you wish to achieve, why switch? In fact, its compatibility with a large myriad of printers and its ease of use when it comes to combining layout, colour management and spot processes is why CorelDRAW is loved so much by the signage industry. Illustrator’s loved by the commercial graphics industry predominantly because of how flexible and interoperable it is. InkScape’s loved by open-source diehards. I know how to use all these apps. Why? Because I don’t obsess or pigeonhole myself into a tool. I obsess about processes and focus on how I can get the most out of what I have.

My point is simple. Thinking like a designer doesn’t mean posing about how good your Photoshop skills are. It’s how good you are at solving problems with whatever tools a company has at hand. It’s about dealing with the conditions you already have. Get in, build a process and get stuff done.

Rule 7: Get some good idols.

When it comes to learning about new processes and obsessing over broad concepts, whilst also leaving your ego at the door, it’s important to get yourself some good idols. Even if they aren’t in your field. Mentors and role models can come from anywhere. When I was in university? I immediately paired up with my next-door neighbour, a Screen Academy student, to learn about how to frame and align shots properly, and we shared ideas between ourselves and get a good idea on how to shoot stuff. When I entered the professional world I am in now, I saw my bosses not as my employers, but as mentors who would show me the ropes on how the field works, and then I would take my pre-existing skills and shape them to suit.

70% of what you learn comes from actually doing the thing you want to do, but 20% comes from learning from others who already know about doing the thing in the first place, or have done the thing in the past and have shared their knowledge with you. Only 10% of what you actually learn comes from books, hard materials and formal training.

I also happen to have a bit of a penchant for online politics, and one thing I say to people is simply this.

An inch of praxis is worth more than a mile of theory.

You can bury your head in a thousand books about Karl Marx and talk about building a future for a better world, but when was the last time you considered the truth behind that man. Yeah, I know, this is now a Marxist design page. Deal with it. But little did people know that half the reason why he came up with the conclusion that Capitalism was destined to fail, which formed the basis of his critique on capitalism, is entirely because he was an expert on capitalism.

That’s right, online socialists. Marx was one of those very speculators you hate.

I have, which will surprise you not a little, been speculating — partly in American funds, but more especially in English stocks, which are springing up like mushrooms this year … [and which] are forced up to quite an unreasonable level and then, for the most part, collapse… in this way, I have made over £400 and, now that the complexity of the political situation affords greater scope, I shall begin all over again. It’s a type of operation that makes small demands on one’s time, and it’s worthwhile running some risk in order to relieve the enemy of his money.

Karl Marx in a letter to Frederich Engels

The simple fact that he had a profound expertise in economics is the sole reason why people respected the man’s theories. Remember, his trading decisions were entirely to directly attack capitalists themselves and bet against their wishes. He was the very first man to use economics as a weapon.

Essentially, revealing that in order to intentionally defeat capitalism, you need to become a ruthless capitalist and bet against the concept entirely. You need to become an expert, have good indent, and more importantly, check your ego at the door. It’s kinda why I like the man’s ballsiness. I will never proclaim to be a “Capital C Communist” these days, as that word carries context that is as thick and wide as a container ship blocking the Suez Canal. But, I see huge merit in understanding his theories, which is why I enjoyed his works. It’s also why I enjoy the works of Noam Chomsky, Michael Parenti, Ho Chi Minh, Slavoj Zizek, and as a real hilarious contradiction, Anthony Robbins and Jordan Peterson.

Why? because it’s good to have idols, but it’s not good to idolise them. Don’t obsess about people or tools, obsess about ideas. Zizek says it himself when he doesn’t call himself a Marxist despite being on that side of political discourse. For reference, Loom carries a copy of the Little Red Book in his bag just to trigger people for the comedy of things. A real Zizek-esque move.

As a designer it’s important to idolise ideas over people. To quote one of the people who I respect the most, considering that I worked for his company for many, many years before his death.

Making mistakes is the privilege of the active. It is always the mediocre people who are negative, who spend their time proving that they were not wrong.

Ingvar Kamprad, the late CEO of Ingka Group/IKEA

So to those out there in the world obsessed with cancelling people. I get why it’s important, but the whole idea behind cancel culture is not to prop up individuals or smack individuals down or to give companies praise for being woke and good and demonize others that are shit and bad, it’s to set the standard of an ideal world where people practice what they preach and tell the damn truth. No company is truly perfect, and nobody can ever be 100% perfect, as to be perfect is to be nothing.

There is no such thing as a perfect saint. Everyone’s a sinner, because to sin is to be human. However, to be a revered and likeable person, focus and intend upon improving yourself.

Stop acting like a designer, and start thinking like one.

Beano out.